April 1, 2021

How unique or specific does a game mechanic have to be in order to qualify for a patent?

For aspects of any software-based game to be patentable under UK law they must satisfy certain criteria. Amongst other things these criteria require an invention to be unique in that it must be novel – i.e. it cannot already be in the public domain or form part of the “state of the art”. Further, the innovation must contain an inventive step and cannot simply be an obvious development over the state of the art.

Attempts to patent aspects of software-based games may also be challenged as falling into a category of subject matter that is excluded from patent protection as a matter of public policy. For example, it is generally not possible to receive protection for a method of playing a game or doing business or for a computer program BUT this only applies to the extent the invention itself relates to the excluded subject matter as such. This ‘as such’ qualification is an important one which can allow for inventions related to excluded matter to be patented, provided they can be shown to have sufficient “technical effect”.

Typically a game “mechanic” refers to the rules that govern the player’s actions and the game’s response to them, essentially specifying how the game will work for people who play it. The rules of the game alone are unlikely to be patentable as they would be considered excluded subject matter. However, the specific implementation of those rules in an innovative way may be patentable, if it has sufficient technical character or provides a sufficient technical effect. In other words, if a particular problem in a game’s operational design needs to be addressed using a new and inventive technical or engineering-based solution, whether developed using middleware or otherwise, then that solution may be patentable notwithstanding that it is implemented in the context of a computer game.

Technical effects that have conferred patentability on otherwise excluded computer program inventions include (1) affecting a process which is carried on outside the computer, including graphics innovations; (2) inventions that operate at the level of the architecture of the computer, (3) causing the computer to run in a new way; and (4) making the computer a better computer in the sense that it runs more efficiently and effectively.

How common are gameplay-related patents?

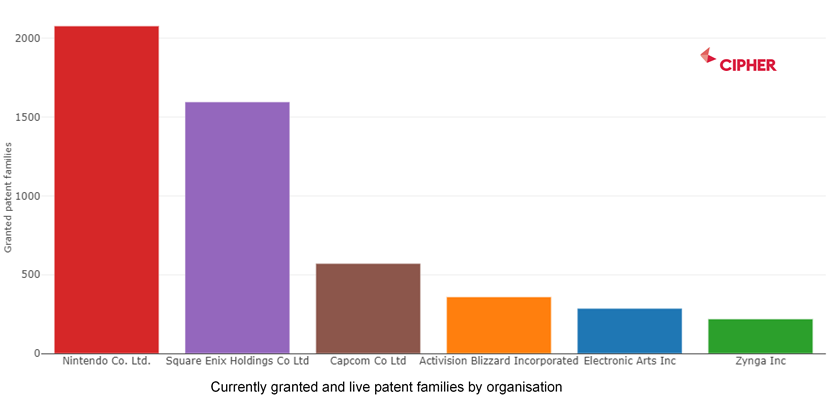

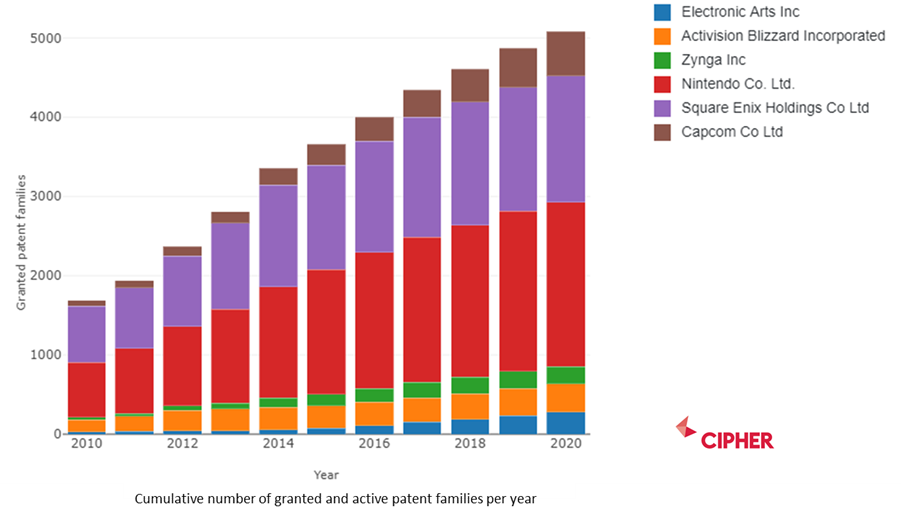

While requirements around patentability normally exclude inventions purely related to the rules of “gameplay”, it is not uncommon for computer games companies to patent technical aspects of their products, both relating to their software and, where applicable, their hardware (consoles, controllers, sensors, etc). Big tech companies that also operate computer game divisions have vast patent portfolios, and no doubt some of those inventions will underpin both game and non-game related technology. But pureplay computer games companies have also been actively pursuing patents. We take a look at a small sample below.

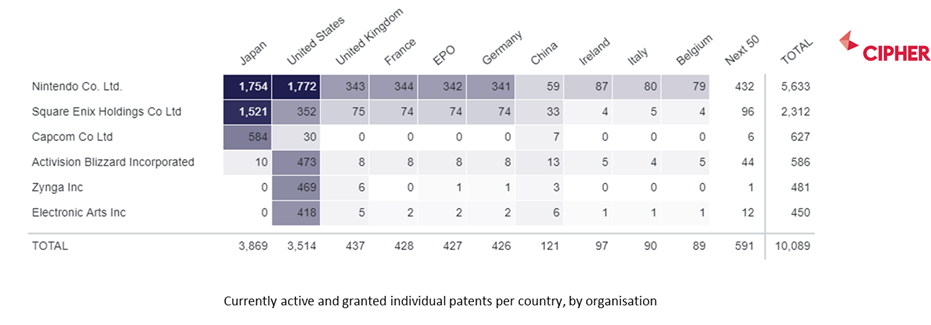

Japanese companies tend to have some of the largest portfolios of granted patents in the sector. Historically, large electronics companies in Japan have actively pursued patent protection, a trend that has seemingly spilled over into computer games particularly where those companies also produce hardware. However, even outside of Japan most computer games companies have been increasing their patent position in recent years.

It is notable that US-based companies tend to only protect their inventions in their home territory. Generally, this effective lack of protection in the UK, Europe and Asia means that this technology is free for anyone to use in those territories.

However, it remains to be seen whether companies are leveraging this freedom to use their competitors’ technology in those countries where patent protection has not been sought. Game publishers will no doubt want to release the same game unaltered in all markets simultaneously and creating a US version that avoids patented technology that supports a game mechanic feature may be commercially impractical and technically unfeasible (for example in relation to MMO games). Nonetheless, there are risks in having such limited, country-specific protection for a technology that is sold and used globally.

How would a games-related patent apply to a piece of business software, are they effectively dealt with the same way?

Depending on how the patent is drafted, it is feasible for a software patent that is generated in one industry to apply to products in another. This is particularly the case for computer-related innovation which can have applications in a variety of commercial settings. For example, patents relating to graphics processing generated by a computer games company could equally read onto products such as simulations used for training or structural design software. This can provide patent owners with an opportunity to develop licence revenues outside of their traditional sectors.

Are these patents usually hyper specific, so other developers can create similar but non-infringing technology, or can they be used more broadly to block the use of an entire technical field?

It is a mixture. With a nascent technology it is generally easier to obtain broad protection as there is very little pre-existing that is similar in operation. That makes the test for novelty and inventive step easier to satisfy in respect of the fundamental aspects of the technology, aspects which will need to be used by a third party irrespective of the specific application. It can be difficult to avoid such third party patent risks and developers may need a wholesale change in technical direction or to take a licence from the owner (if possible). In established technologies, patents may be granted for more incremental developments which, though inventive, are narrower in scope (e.g. for a specific application or method of use). The more specific the scope of the patent claim, the easier it can be for a developer to alter the work product to avoid infringement without materially impacting functionality.

Are there differences in UK and US patent law that developers should be mindful of?

Yes, but the requirements (e.g. of what qualifies as the necessary technical effect or contribution) can change in both countries. Before 2014, the US Patent and Trade Mark Office was typically seen as being an easier place to obtain software-related patents than elsewhere in the world. However, in 2014 the US Supreme Court judgment in Alice v CLS Bank materially reduced the ability of patentees to protect software and business method related inventions. Seven years later, there is now some evidence to suggest this trend is starting to reverse and there is plenty of evidence that computer-related inventions are rising in all jurisdictions because of new software innovations, such as AI.

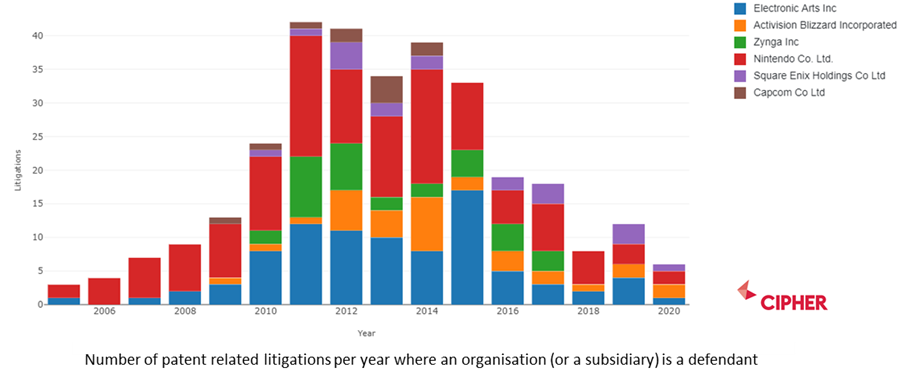

How often are such patents enforced?

Frequently, though it is not always other computer games companies that threaten or bring infringement proceedings. By far the majority of litigation relating to computer games patents is brought by companies that acquire game technology patents but do not produce technology themselves. These “non-practising entities” (NPEs) are prevalent in the United States and pose a particular threat to all games companies because they are not vulnerable to an infringement counterclaim (i.e. because they do not make anything).

Since the US Supreme Court’s decision in Alice in 2014 and as a result of cross industry efforts to keep patent assets away from NPEs, the number of enforcement actions has fallen. However, the risk continues to present problems for the industry as many companies remain willing to sell their patent assets to NPEs.

Aside from infringement litigation, it is not uncommon for computer games companies to bring legal proceedings to proactively revoke or invalidate third party patents, on the basis that they were incorrectly granted. This is used against the patent portfolios of competitors and NPEs alike, as a response to the threat of infringement litigation. For example, in the US computer games companies regularly bring inter-partes post-grant review proceedings in front of the US Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). A similar opposition mechanism also exists at the European Patent Office for the relevant UK and European patents.

Though patents are, at their core, exclusionary rights enforceable against third parties, it is worth remembering that they can provide value in ways other than enforcement or the threat of enforcement. For example, they can form the centrepiece of joint development or technical collaboration projects, and may also be used by their owners in order to benefit from jurisdictional tax-related rules designed to promote innovation (e.g. the Patent Box regime in the UK).

When designing their next game, how concerned should developers be about gameplay patents they may not be aware of and how best should they protect their own innovation?

Putting the NPE risk to one side, some computer games companies appear to be building patent portfolios for defensive reasons (i.e. to be able to retaliate if it is sued by a competitor), rather than pursuing an aggressive litigation strategy. That said, while patent litigation in the computer games industry is nowhere near as active as, say, the telecoms or pharmaceutical sectors, third party patent rights, if validly granted, pose a significant risk where they read on to your product. Strategic and commercial motivations over whether to enforce a patent or not can change quickly and so it makes sense to keep an eye on risks presented by third party assets if possible. If you become aware of a problematic competitor patent during the product development design phase, it may be possible to avoid infringement by ‘designing around’ the patent claims, depending on the specificity of the claimed invention. If you are collaborating with another company, you should think carefully up front about how to contractually allocate the risk of any resulting work product being the subject of third party patent enforcement proceedings.

As regards obtaining patent protection, the more difficult the problem that needs solving and the more technical the solution needed to solve it, the more you should consider filing for patent protection. Should a material dispute arise with competitors, a strong patent portfolio can only help to strengthen your bargaining position, and if you don’t have one, it will be too late to rectify. But there is a balance to be struck; building a patent estate can take effort, time and money. Much like in other sectors, computer games companies should look to develop an appropriate patent strategy that reflects their industry, their technical innovation and their resources. The strategy should account not only for the risks of litigation, but also the opportunities to leverage patent value through licensing (e.g. in technical collaborations) and in other commercial contexts (e.g. to benefit from specific tax rules).

This article was first published in Biz Media – March 2021

Expertise