July 22, 2024

Following a request from the Government in 2022 (on which we reported here), the Law Commission has published a scoping paper on Decentralised Autonomous Organisations (“DAOs”), examining how they can be characterised and how the law of England and Wales can accommodate them.

What is a DAO and which type of DAO are we talking about?

One of the central challenges of any such accommodation of DAOs by the legal system is something that the scoping paper recognises at its outset, namely the difficulty in reaching a consensus as to what, in fact, a DAO is. The Law Commission writes that “they are difficult to describe, practically or legally, largely because the term “DAO” does not refer to any one type of arrangement. Commentators disagree over what characteristics an arrangement must have in order to be properly called a “DAO”, and many arrangements using the term look very different from the DAO ideology as originally conceived.”

As we have discussed previously (here and here), at their most basic, DAOs can be described as an arrangement involving multiple participants whose functions defined to varying degrees by blockchain systems, smart contracts or other software-based protocols. DAOs were originally conceived as an alternative to traditional organisations with centralised decision-making structures. In a pure DAO, no single individual or group holds control, but instead it operates based on the ‘democratic’ collective decisions of its participants using a set of rules encoded into smart contracts on the blockchain protocol that governs the DAO.

As well as being decentralised, as the name suggests a DAO is also autonomous insofar as its activities, functions and decisions can operate automatically according to the rules and procedures written into the relevant underlying protocol governing the DAO. A DAO can therefore automatically execute decisions transparently based on these rules without the ’interference’ of human discretion.

The autonomous element of DAOs is not limited to their being self-executing, but also is a reference to their being ‘self-sufficient’. As the Law Commission explains, DAOs “grew out of a desire to operate other than in [the] highly regulated, state-controlled environment” of comprehensive laws and regulations applying to other forms of organisations such as private companies. To some, this means that a central tenant of the DAO philosophy is that they are free from outside laws or real-world intervention.

The paper explains that, in reality, most DAOs that have been brought into existence so far do not operate in a fully autonomous or decentralised manner:

- they still rely on individuals to perform certain tasks that automated processes cannot;

- there is usually a central group of people – often the original software developers or those who founded (and funded) the project over which the DAO governs – who exert a significant degree of control of the DAO’s governance and operations (whether by continuing to have significant tokenholding in the project or through governance token rights); and

- contrary to the original conception of DAOs – one in which they would be fully digital and have no real world assets or substantive offchain activities – many DAOs have significant dealings with the “off chain environment, purportedly entering contracts and holding real-world (off-chain) assets”.

In this context, the Law Commission states that “it is not possible to “opt-out” of national and international laws merely by setting up a [DAO]. Indeed many [DAOs] have started to use existing legal forms, such as limited companies, to benefit from the separate legal personality and limited liability they afford, and to assists with matters like tax certainty and regulatory compliance”.

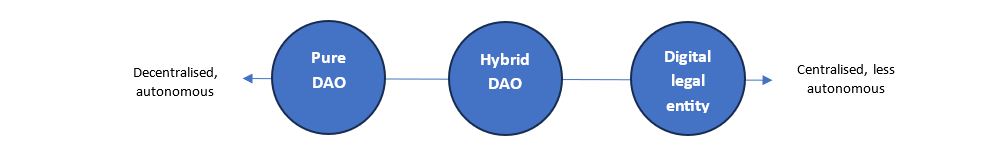

The scoping paper identifies and analyses three broad categories of DAOs that exist on along a spectrum depending on how decentralised and/or autonomous they are. The Law Commission then considers how to categorise each type of DAO and the legal relationships between the various actors involved. As it explains, only then can the legal system hope to address questions such as who is liable when things go wrong, what duties the participants owe to each other and third parties, and what regulations, taxes, and jurisdictional rules might apply to the organisation.

1. ‘Pure’ DAOs

A ‘pure’ DAO, as the Law Commission explains, “sit[s] at the more decentralised and autonomous end of our spectrum: they are decentralised and reject dependence on law and legal institutions for their existence”. A critical feature of a pure DAO is that it deliberately does not use any legal entities within its structure, relying instead on technology to set the rules according to which the participants in the organisations interact. Indeed, the Law Commission posits that some pure DAOs do this “consciously hoping to avoid legal characterisation entirely”. However, the paper states that “it is nevertheless possible (and arguably necessary) for a group of people who organise themselves as a pure DAO to attract some form of legal characterisation”.

The legal characterisation of a pure DAO and the obligations that fall onto its participants will therefore depend on the facts and on the “application of long-established, technology-neutral tests under the general law”:

- A pure DAO “might be characterised as a general partnership and its use of novel technical features, such as the business being governed through on-chain voting, does not preclude this”.

- Alternatively, if characterisation as a general partnership is inappropriate due to the decentralisation of governance and their having pseudonymous and changing members, a pure DAO might instead be characterised as an unincorporated association, in which its members will generally only be liable for their own acts or those of their agents, and do not owe each other duties in the same way as partners do under a general partnership.

- Even if a pure DAO does not amount to a general partnership or unincorporated association, its participants may nevertheless have obligations to one another under contract (whether written down or not).

- Further, even in the absence of being able to establish a contractual relationship, relations between participants and third parties “will still be subject to other legal analyses and so participants may still have liability, for example, in torts such as common law negligence, or by way of fiduciary duties, unjust enrichment or under a trust”.

Fundamentally, the paper is clear that a pure DAO – and its participants – will not escape the confines of existing legal frameworks in England and Wales: “because [the tests of legal categorisation] are technology neutral, they do not cease to apply because the DAO participants operate on a blockchain rather than through in-person interactions. DAOs will neither be unfairly exposed to, nor unfairly protected from, the relevant characterisation and legal consequences in England and Wales merely because of their use of novel technology”.

Bitcoin is an example of a pure DAO without any centralised control or legal entity behind it, and as we reported on here, English courts are determining whether participants have liability or duties to digital asset owners, or whether the Bitcoin protocol is just software maintained by developers who aren’t accountable to or liable to provide any remedies to Bitcoin holders.

2. ‘Hybrid’ DAOs

A ‘hybrid’ DAO combines elements of a pure DAO with one or more legal forms or entities. This is commonly called ‘wrapping’: the pure DAO elements of the organisation are ‘wrapped’ within a recognised legal entity structure. This is often done so as to better protect the DAO’s participants from liability or to interact with the ‘off-chain’ world by using existing legal structures that recognise separate legal personhood for the legal entity from its members. For example, the legal entity may hold intellectual property or employ staff, while the “greater part of the [hybrid DAO’s] governance is likely to remain within the pure DAO element”.

For those participating in a hybrid DAO, key questions will be what type of legal entity or entities to use and in which jurisdiction to establish them. Some jurisdictions will be more advantageous than others: the Law Commission points out that states such as Wyoming and the Marshall Islands have introduced DAO-specific forms of legal entity to attract DAOs, meanwhile jurisdictions such as England and Wales have seen essentially zero DAOs set up. This is something that we have explored previously here, and the Law Commission’s research suggests that this could be due to requirements for transparency (such as anti-money laundering requirements and having to identify individuals) as well as the lack of suitable legal vehicles with features and requirements that align with the functions and operations of a pure DAO.

Other jurisdictions such as Switzerland and the Cayman Islands offer foundation, association, or ownerless legal entity structures that, in addition to other features of those jurisdictions, are conducive to being selected as the legal wrapper for a pure DAO and have no doubt driven its attractiveness as jurisdictions for token projects to establish their hybrid DAO. Aragon, Solana and Internet Computer implement a hybrid DAO structure with Switzerland entities wrapping pure DAO project functionality.

3. ‘Digital legal entity’ DAO

A ‘digital legal entity’ is an incorporated legal entity which “makes use of technology such as Distributed Ledger Technology and smart contracts in its formal governance and/or operational arrangements.” The paper states that these types of entities are still “largely theoretical in this and most jurisdictions due to statutory restrictions on the form of, for example, shareholdings and fund interests”.

The Law Commission’s recommendations for DAOs

The paper concludes by making clear that at this stage its purpose was to “simply identify how the current law is likely to apply to DAOs”. It has not been asked to make formal recommendations for law reform. That said, the Law Commission states that its view is that:

- Critically, England and Wales does not currently need to develop a DAO-specific legal entity: “This is in part because there is no consensus around what such an entity should look like and where its parameters should lie, and in part because of the general desirability of organisational law remaining technology neutral”.

- It isn’t convinced by arguments to relax legal, regulatory or tax treatment for DAOs compared to traditional organisations: “The case for offering DAOs different, and potentially less burdensome legal, regulatory or tax treatment compared with traditional organisations has not (yet) been made out.”

- Suggesting regulation assuming a particular type of DAO may stifle innovation, particularly as DAOs and their forms continue to evolve: “There is a risk that in attempting to accommodate a particular technological development, ad-hoc and technology-specific legislation will obstruct the very dynamism it is trying to facilitate”.

Instead of developing a DAO-specific legal entity for England and Wales, the Law Commission recommends the following next steps to accommodate and promote the growth of DAOs in England and Wales:

- The Companies Act 2006 should be reviewed in order to determine reforms to facilitate use of technology at a governance level (as they are in DAOs) where appropriate. The law of other business organisations such as LLPs should also be reviewed with the same aim.

- Determine whether the introduction of a limited liability not-for-profit association with flexible governance options would be a useful and attractive vehicle for organisations in England and Wales, including non-profit DAOs.

- Proceeding with the Law Commission’s planned review of trust law under the law of England and Wales. While this will consider trusts in general terms rather than in the DAO context specifically, this will consider arguments for and against the introduction of more flexible trust and trust-like structures in England and Wales, including in relation to token projects.

- Government should review anti-money laundering regulation in England and Wales to consider whether the same policy objectives can be achieved in a manner more compatible with the use of distributed ledger and other technology.

English law reform to recognise DAOs

Of the many DAOs that exist today, hardly any of them are in the UK, and enormous value has already flowed through, been created, used and sometimes lost by DAOs as the vehicle of choice for Web3-native proponents. Significant questions arise for the role played by English law and the common law on shaping the use and recognition of DAOs, which if left unanswered could see the UK left behind as a jurisdiction that encourages blockchain-related investment and innovation.

The law of England and Wales does not presently feature a DAO-specific legal entity. In contrast with other jurisdictions that have certainly made amendments to their statutes regarding the legal, regulatory or tax treatment of DAOs compared to traditional organisations, England and Wales have not taken such steps and nor does the Law Commission suggest that it should. Currently, pure DAOs may essentially be treated legally as an unincorporated association or general partnership, with additional obligations under contract, fiduciary duties, tort or trust arising depending on the circumstances.

The web3 community would welcome the development of a legal entity under the laws of England and Wales that could be used as a legal wrapper to create hybrid DAOs, but whether this will drive adoption and establishment of DAOs in England and Wales will depend on its legal, regulatory and taxation treatment, particularly in comparison with its treatment in other jurisdictions.

To read the scoping paper in full, click here.

Expertise